Merida: Uxmal, Kabah Ruins & Cenotes

Archaeological Sites

Uxmal and Kabah are two remarkable Maya archaeological sites in Mexico’s Puuc region, celebrated for their intricate stone mosaics and elegant architectural style. Uxmal is the larger and more famous of the two, home to the grand Pyramid of the Magician and richly decorated buildings featuring masks of the rain god Chaac. Kabah, located along the ancient sacbe (Maya road) connecting it to Uxmal, is best known for the Codz Poop, a palace covered with hundreds of Chaac masks. Together, they offer a vivid glimpse into Maya engineering, religious beliefs, and the importance of water in this dry landscape.

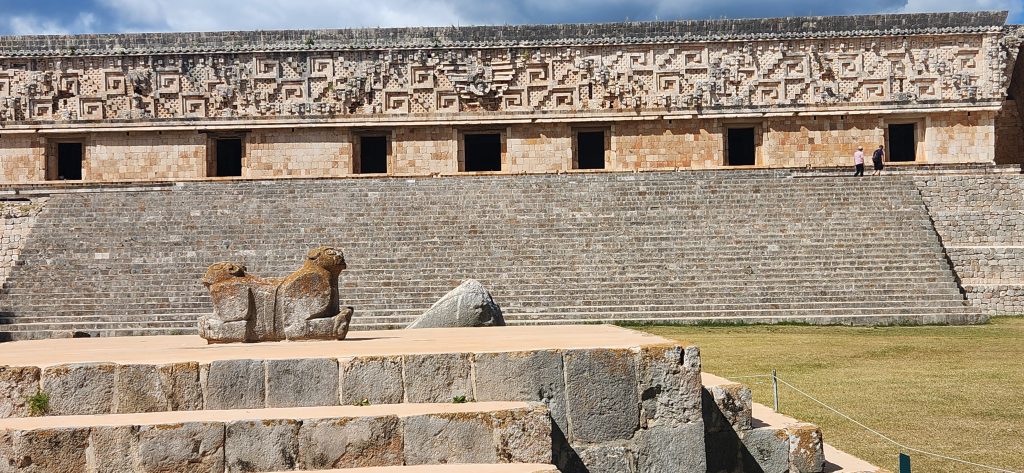

Uxmal

Uxmal was a major Maya city in north-west Yucatán, Mexico, that flourished between the 6th and 10th centuries CE. It is known for its outstanding examples of Puuc style architecture, such as the Pyramid of the Magician, the Nunnery Quadrangle, and the House of the Governor.

And, yes….there were lots of steps. Wasn’t so bad going up, but coming back down was a bit tricky. In one spot, I took the cowards way out and came down on my bottom, step-by-step.

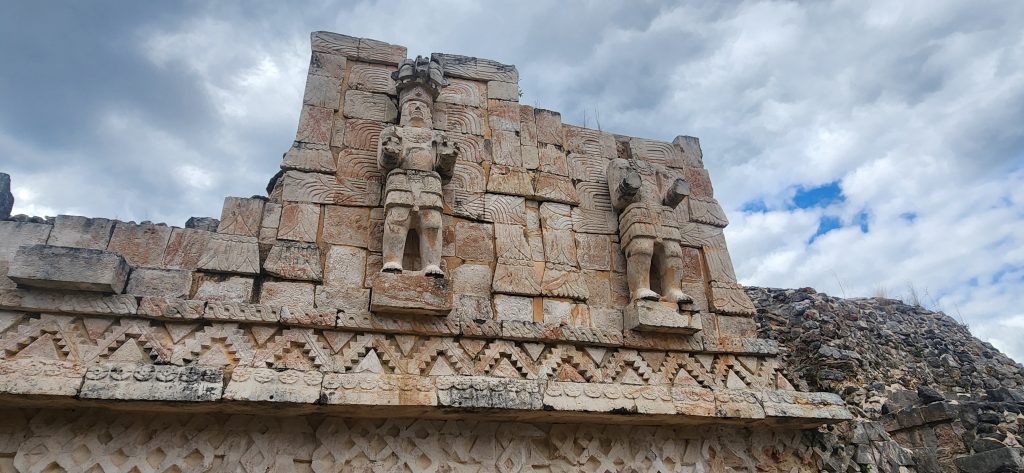

Kabah

Kabah is a Maya archaeological site in the Puuc region of western Yucatan, south of Mérida. It was incorporated together with Uxmal, Sayil and Labna as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1996. Kabah is south of Uxmal, connected to that site by an 18 kilometres long raised causeway 5 metres wide with monumental arches at each end. Kabah is the second largest ruin of the Puuc region after Uxmal.

The Chicxulub Crater and the Formation of the Yucatán Peninsula’s Cenotes

The Chicxulub crater is a significant impact structure located beneath the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico. It was formed approximately 66 million years ago when an asteroid, estimated to be 10 to 15 kilometers (6 to 9 miles) in diameter, collided with Earth. This event is widely believed to have triggered the mass extinction that wiped out about 75% of all species, including the non-avian dinosaurs.

This even not only triggered a mass extinction but also played a key role in shaping one of the most iconic geological features of the Yucatán Peninsula: the cenotes. These stunning natural sinkholes, which dot the landscape of the peninsula, are a direct consequence of the asteroid’s impact and have become important both for their ecological and cultural significance.

The crater was discovered in the late 1970s by geophysicists Antonio Camargo and Glen Penfield, who initially sought petroleum. The connection between the crater and the extinction event was confirmed in 1990 through geological samples that showed signs of an impact origin.

The Impact and Formation of the Crater

The asteroid that struck near present-day Chicxulub created a massive crater over 150 kilometers in diameter. When the asteroid hit, it vaporized the surface rock and displaced an enormous amount of earth, creating a central uplift and forming what is now a buried impact structure.

The region’s geology, primarily composed of porous limestone, was greatly affected by this impact. Over millions of years, as water eroded the fractured rock left behind by the impact, underground rivers began to form. This network of subterranean rivers gradually dissolved the limestone, leading to the collapse of surface layers and the formation of cenotes—sinkholes filled with fresh water.

The Cenote Ring: A Visible Remnant of the Impact

One of the most fascinating features left by the Chicxulub impact is the Ring of Cenotes, a semicircular alignment of cenotes that closely follows the outer rim of the crater. This ring is believed to have formed because the asteroid impact fractured the ground in a circular pattern. Over time, these fractures allowed water to flow through and dissolve the limestone, creating the cenotes in this distinctive ring-like formation.

This unique arrangement of cenotes is not only a geological testament to the asteroid’s impact but also provides insight into the ancient groundwater systems of the region. Many of the cenotes in this ring offer explorers and divers the opportunity to see geological formations that date back millions of years, including the rocks displaced by the impact event.